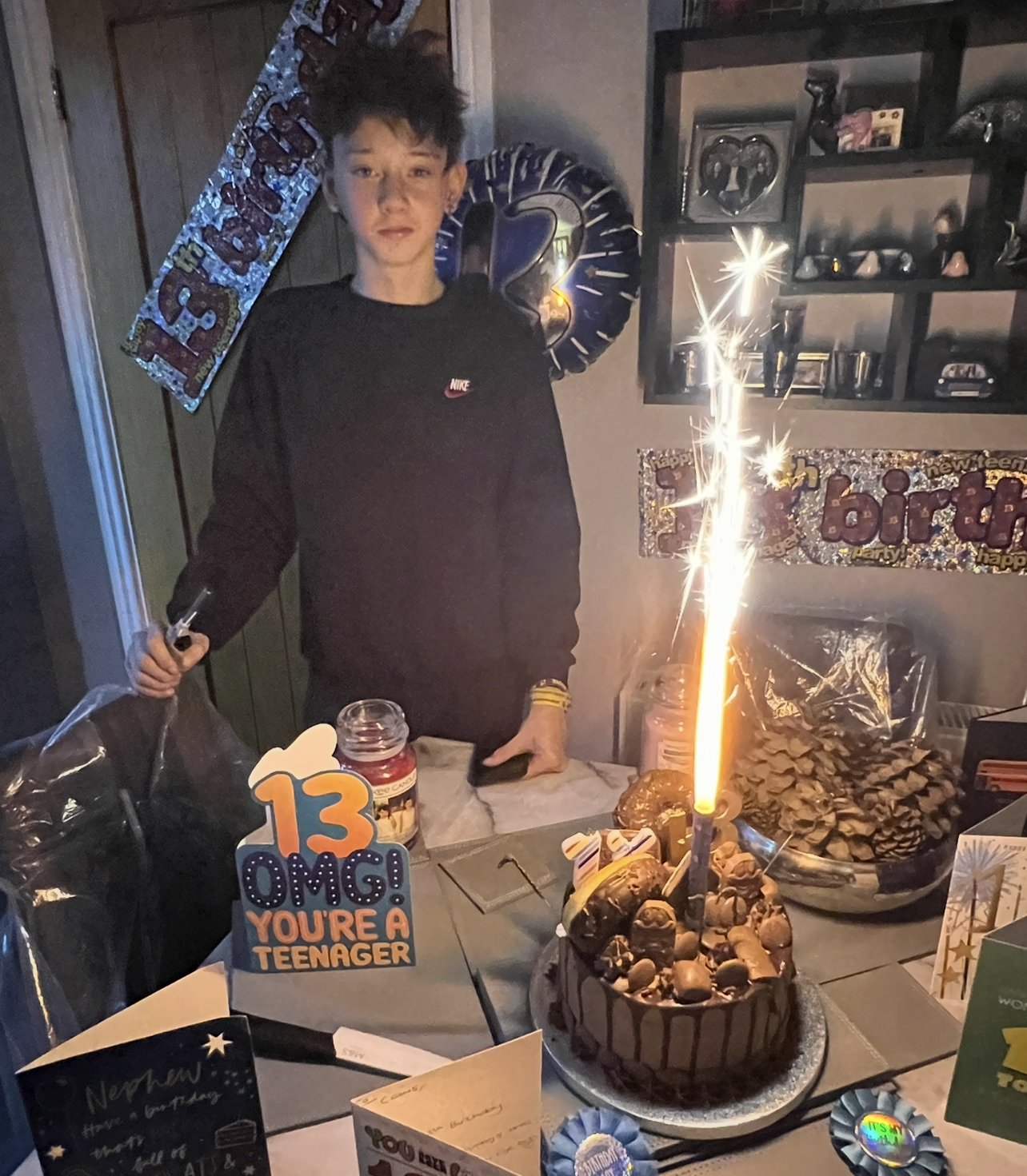

We’re grateful to Rachel, a busy mum of seven, for sharing her experience with her son, Caius, who has just celebrated his 13th birthday, and explaining why she feels there needs to be far greater understanding of what it means to live with a childhood liver disease.

When Caius was two weeks old, our midwife expressed concern about his slow weight gain and his jaundiced appearance. She referred us for tests at North Staffs Hospital and, after three days there, he was sent to Birmingham Children’s Hospital where biliary atresia was diagnosed. Caius had his Kasai procedure when he was four weeks old. Fortunately, this was a success, and he has not yet needed a transplant, although we are conscious that this is a probability for the future. He has other complications resulting from BA, including portal hypertension and varices, but these have not required banding yet. So, in terms of physical health, I’m conscious that things could be much worse. We go to Birmingham once a year and don’t have to spend weeks on end in hospital as I know other families do.

I still feel, however, that the impact of his diagnosis is huge. Neither I nor my husband, Mark, had never heard of biliary atresia before Caius’ diagnosis. In fact, when it was initially being investigated, the consultant told me not to Google it due to the negativity of many outcomes. Once it was confirmed that it was what he had, we looked it up. I found it very scary and still do.

The effect on the family was instant. Mark was about to start a new job, but had to delay it for a month – there was so much to cope with at home. I remember when Caius came home from hospital after his Kasai that my other children had to stay with grandparents for a time when because they had a bug and Cai couldn’t risk infection. I suffered from depression after Caius had his Kasai and the consultant referred me to the doctor because she could see I was struggling, not just with worry over Caius but the guilt of leaving my other children to stay by his side.

Initially it was felt that the Kasai operation had failed and Caius need a transplant quite early and I remember one doctor suggesting that we put him into care so we could be with the other children as he would need to be in hospital for months. I remember my husband crying when this was put to us and he never cries. Obviously, I refused that and fortunately Caius improved once he was on antibiotics.

He had to see nurses three times a day for medication, they would come to our house to administer it. He had that many blood tests that his veins had collapsed and they had to start using his feet. He used to have a phobia of anyone dressed in blue because of all the nurses he had seen and the association with needles. He would cry uncontrollably. This went on for months and months. We had to feed him special milk through a tube to help him gain weight and I can still recall all the boxes of milk and equipment stored in the extension.

Fast forward to today and Caius is in Year 8 at middle school; he’ll go to high school in September. Having a liver condition has given him an anxiety about taking part in PE. There are some activities he is unable to do like contact rugby or boxing, but he tries his best to avoid other sports as he has been advised to avoid aggressive physical contact. He knows how seriously other boys take their sport, so he just tends to distance himself and spends a lot of his time with girls for this reason. He finds boys too boisterous and it worries him. It is this anxiety coupled with the knowledge that he will probably need a liver transplant at some unspecified point in the future that he sees a therapist once a week and I know he finds this helpful.

Although Caius has a lot of interests and loves learning about stuff which interests him – he wants to be an architect one day – he does have difficulty concentrating and can be easily distracted in class. Whether this is connected with his liver condition, I don’t know. The school are fully aware of it, but I’ve never been asked to discuss it or provide further information after completing his initial care plan when he first joined. Even now I’m shocked at how many of his teachers are not even aware of his condition. They certainly don’t understand the mental health implications of it or appreciate the effort he makes to keep close to 100% attendance – this is never recognised. I do appreciate that the school may not have the resources to put in place the kind of support we would ideally like, but I’m sure if he happened to have a chronic health condition which was more widely known, there would be a lot more understanding.

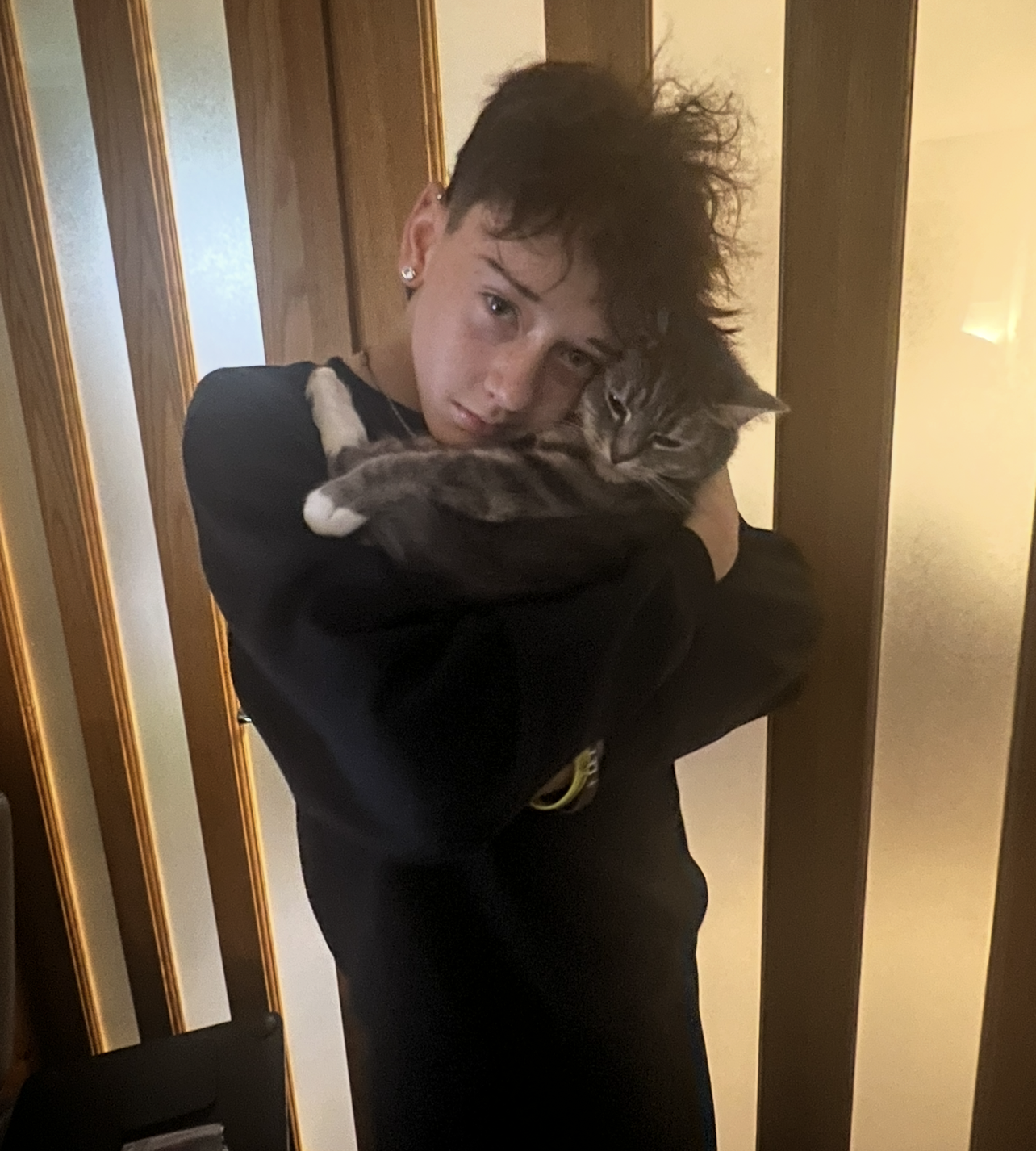

Outside school, Caius is a normal cheeky teenager. He loves his cats, films, eating pizza, Amy Winehouse, playing video games, badminton and spending time with family and friends – there’s always a houseful here! As the youngest of seven, he can stand up for himself. I think his siblings forget about his condition most of the time because to look at him, you wouldn’t know there was anything wrong, but I know that if we were to get ill, they would all support him fully.

As for me, I find Caius’ condition is always in the back of my mind. I try not to dwell on things, but the future worries me. Will he be able to finish school before his transplant? If not, will he have to repeat years, holding him back from his peers?

These are the issues that the outside world doesn’t really understand because Caius doesn’t look ‘ill’. It’s the reason I believe that greater awareness and understanding of conditions like biliary atresia would help young people like Caius, which is why I’m sharing my story.

It’s exactly 13 years since Caius had his Kasai operation and we are so thankful to the NHS staff who saved his life that day and for every day we have had with him since. They gave him the opportunity to grow and live a relatively normal life despite all the obstacles he has faced, and we shall continue to encourage him to make the most of every opportunity which comes his way.